The fruits of the last year and change of my, Sean Keeton’s, and a few other Dread Ringers' labor finally made its way to the App Store and Google Play last December. Now three months have gone by while I too infrequently found time to work on this post-mortem. I’m forcing myself to wrap it up today, lest the game be long forgotten by everyone but its author before this post-mortem is published.

Some of my previous games have been post-mortemized in GDC lectures, but I don’t feel that Spellwood was technically or financially innovative enough to merit a seated audience (and I don’t much like giving presentations to boot), so Spellwood gets a blog post instead. I’ll also be waxing a bit historical here and there, so please excuse the nostalgic tone.

Lies, Damned Lies and Statistics

- Development:

- started Oct 5 2011

- shipped Dec 5 2012

- Source files / Lines of code¹ (per SLOCcount):

- core - 154 / 18,061 (Java)

- ios - 5 / 751 (C#)

- android - 11 (+4 generated) / 1,258 (Java)

- server - 37 / 2174 (Scala), 7 / 269 (Java/GWT)

- tests (in core and server) - 20 / 1189 (Scala)

- Images:

- source - 4669 files, ~834MB

- processed - 747 PNGs, 27 JPGs, 68.8MB

- Sounds:

- source - 32 files, 23.7MB (as WAVs)

- processed - 32 files, 2.2MB (as MP3s), 3.3MB (as CAFs)

¹ Note that the game is built using PlayN and Triple Play which do substantial heavy-lifting (weighing in at 46kLOC and 10kLOC respectively, again per SLOCcount).

Pre-history: Platforms

In early 2011, I set out to create the next generation of game development tools for Three Rings, to replace the stalwart, but aging, trio: Narya, Nenya and Vilya (but not the still spry Clyde). One big impetus for this nextgen toolkit was to support deployment to HTML5 and mobile devices (at least Android and iOS).

The new tools took shape in two libraries: Nexus a distributed application framework, to replace Narya, and Jiggl a 2D scene-graph game engine built directly on OpenGL, to replace Nenya. Vilya’s replacement would come later as new games built high-level systems based on Nexus/Jiggl that could be abstracted without too much code weirding. Both of these libraries would still be written in Java, but structured such that they were GWT-compatible and had backend components for doing low-level things like graphics and networking via JVM/LWJGL, and HTML5/WebGL.

My intention was to support mobile platforms via HMTL5. This turned out to be a bit too “forward thinking”, as HTML5 on mobile devices is still not (as of the publishing of this article) a viable platform for games. Fortunately that bullet got redirected by other twists of fate and didn’t even need dodging.

I started on Nexus in February of 2011, and Jiggl in April. Shortly after Google I/O in May 2011, someone forwarded me a link to a presentation on some Google project called ForPlay. “Gee,” I thought, “that sounds a lot like Jiggl.” Indeed, it was, and they were a lot farther along than I was. They had backends for Android, HTML5/Canvas and even Flash to boot. I didn’t like that the Java backend was based on Java2D, but that could be remedied later.

Not one to particularly coddle my babies, I threw Jiggl out with the bath water and jumped enthusiastically on board the ForPlay train. My first commit was on June 2. Now I have more than everyone else combined (many thanks to jgw, cromwellian, progers, fredsa, et al. for allowing me to stand on their shoulders). ForPlay was renamed to PlayN somewhere along the way, presumably because business people at Google were tired of blushing a little when presenting the technology to partners.

Pre-history: Atlantis and Dictionopolis

I don’t like to work on frameworks in a vacuum, so while I was working on Nexus and PlayN, I was porting the game that I wrote when I was first working on Narya and Nenya: Atlantisonne. (The linked version is a version reworked for Game Gardens a casual game Java framework and hosting service that I wrote after Puzzle Pirates shipped.) I dropped the “onne” for the PlayN version and just call it Atlantis. I’ve become a fan of brevity in my old age.

Just as Atlantisonne eventually gave way to proper Puzzle Pirates development, so Atlantis started to show signs of being too simple to properly exercise the platform and needed to make way for a proper game. I had been toying with an idea of making an RPG where you did battle by solving math problems, and had code named it Digitopolis (after the city in The Phantom Tollbooth). I never considered the idea even remotely commercially viable, but it led me to think about a similar approach using a more well established word-game mechanic instead of math. Mr. Juster already had a codename for the project ready to hand: Dictionopolis!

Prototype and Proposal

I started fleshing out the design in the beginning of October and made the first commit on the prototype on October 10th. By late December the prototype was strong enough to throw at a bunch of playtesters, which I did. I was sure to lower their expectations as to the graphical sophistication of the prototype with the following splash screen:

PlayN didn’t support iOS at that point (and iOS was my primary target platform). For the prototype I built the game in HTML5 with the necessary webkit machinations to get it to feel moderately like a real app when installed to the home screen (which allows one to dispense with all the Mobile Safari chrome). I knew well before then that I would need to get PlayN working on iOS, but that was still on the “later” list.

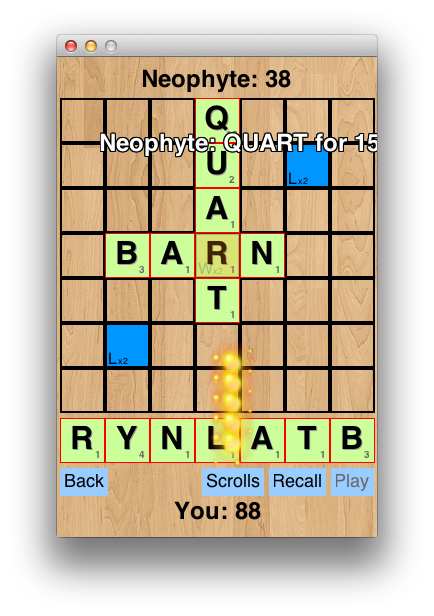

This is what the prototype looked like at that point:

The fact that people found it fun was a good sign. They certainly weren’t being wowed by the fancy graphics. Armed with this positive feedback, I steeled myself for the forthcoming “pitch process”. Three Rings had been acquired by SEGA in November of 2011, and after ten years of doing whatever the hell we damned well pleased, we now had bosses by which we had to run new ideas.

We pitched in a byzantine series of meetings in January and February. Fortunately, the game was small enough (or rather the proposed development budget was small enough), and the idea sufficiently non-radical, that SEGA gave it the green light without a tremendously polished presentation on our part. I was off to the races. This mainly meant that I got a proper artist in March (actually three, and it was a month or so of crowded kitchen before we pruned that down to one artist). It also meant that my work on the platform was now driven by the needs of my new game, and that the game would consume increasingly large proportions of my development time over the next eight months.

PlayN on iOS

Not long after getting the prototype out the door, I decided to take a crack at my longstanding TODO item: “Get PlayN working on iOS.” I had cursorily looked into existing technologies that could be put to this task, and the most promising contenders rolling around in my head were VMKit (a lot of work), XMLVM (more promising, but pretty rough around the edges), and a combination of IKVM and MonoTouch (a lot of moving parts, but the most promising).

I decided to take a crack at option number three because MonoTouch seemed very robust (being based on Mono and having the benefit of a dedicated team working hard to make iOS support commercially viable), and IKVM was a shockingly mature and complete emulation of the JDK on the CLR (Jeroen had been working on IKVM for more than ten years at that point).

I quickly discovered that IKVM was designed to emulate the vast sprawling mess that is the JDK using the vast sprawling mess that is the Desktop profile of the CLR. MonoTouch, on the other hand, only provided the Silverlight profile, which was a substantially stripped down set of APIs that omitted the ponderous bulk of the myriad enterprise APIs that were critical to the mission of consuming large amounts of virtual memory on servers all around the world.

To compound that problem, the JDK has adhered strictly to the “giant intertwingled ball of spaghetti” modularity philosophy during its fifteen years of accumulative development. Thus extracting a core of functionality that works on MonoTouch’s Silverlight profile required going into the OpenJDK with a blow torch, a hacksaw, and a malicious disregard for good software engineering principles. Armed with these tools, I spent two days deep in the jungle and emerged into the bright glorious sunshine with a hacked up version of IKVM and OpenJDK that ran on MonoTouch. Though history may deem me unkind for doing so, I then published the fruits of my labor for all to see: ikvm-monotouch and ikvm-openjdk.

After the initial IKVM and OpenJDK hackery, getting PlayN working was just a bunch of typing. That typing started on January 11th, and by the 25th, I had Dictionopolis running natively on my iPhone. W00ts were w00ted, and I got on with the business of making my game.

Development

Development was pretty smooth for the most part. I was doing all the code, game design, and project management, so that cut down on a lot of arguing. I had a very concrete idea in my mind of what I wanted the game to be, and most of its systems and elements. That was abetted by the fact that just about everything was pretty fun and workable on the first run through (a rarity in my experience), so I didn’t have to do any major backtracking and rethinking.

We did hem and haw a great deal at the beginning about the main character, which resurfaced in the eleventh hour as we redesigned the main character the week we were supposed to ship to Apple. Since everyone loves the pretty pictures, here are some early character sketches — not all meant to be the main character — by Sean Keeton (the art lead), Natalie Butler (who did concept and production art) and Josh Gramse (who did concept art).

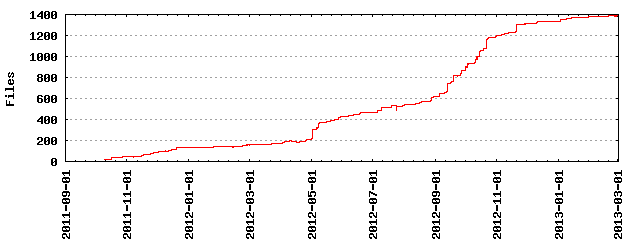

Since I have no especially entertaining anecdotes to relate regarding the development process, I’ll show you some charts instead. Here we can see the inexorable accumulation of files:

I’d show lines of code instead of files, but

unfortunately the massive source dictionaries that I committed to the repository confuse

gitstats (which I’m using to generate these charts). In any case, we can see that

September and October were characterized by a development velocity that can be best described as

“oh crap, we’d better ship this thing soon”. (We were originally scheduled to ship in November, and

then slipped to December due to “marketing-timing” reasons.)

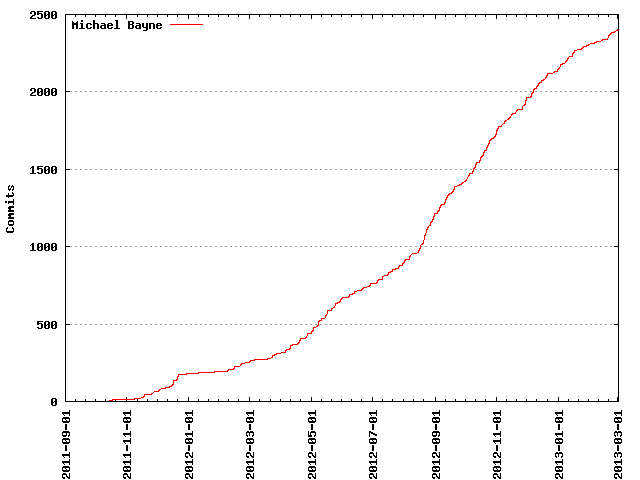

Also this file-based view may be a bit misleading. The graph of total number of commits is a bit smoother and shows slightly less change in velocity as we approach ship:

It’s interesting to see that I’ve made a lot of commits since we shipped in December, but (as the files graph shows) that’s a substantial number of small, tweaky commits, rather than the addition of bunches of new code and media.

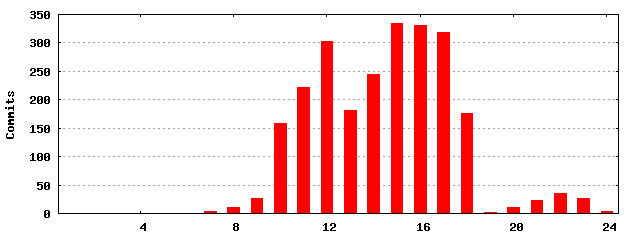

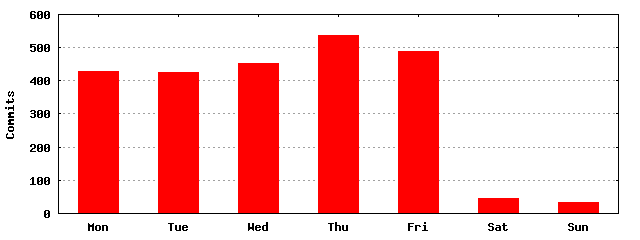

In spite of this acceleration of progress toward the end of the project, I can happily report that I didn’t work nights:

Or weekends:

At least not in any substantial amount.

Closing Remarks

I had a lot of fun working on Spellwood. It also served as the impetus for me to hack a path through a few technological forests, which others have now followed to publish their Java-based games to the App Store.

Spellwood did not take the mobile word game market by storm, as I secretly hoped, but it has found a number of enthusiastic fans. I can also honestly say that I am still enjoying playing it myself, which is rare after being so close to a game for so long.

After spending 2012 bringing a game to life and to market, I’m hoping to spend 2013 being a better steward of the platform that Spellwood was meant to field test. Three Rings has two more games being built on that platform (both much bigger than Spellwood), and hopefully we’ll see more exciting commercial releases using PlayN as well.